In the previous missiological reflection, I described theological reflection as the beginning point of ministry. Missionaries (that is, all Christian leaders) must yearn to know the heart and motivation of God— what God is about in his world and why he is doing what he is doing—so that their ministry aligns with the purposes of God.

In the previous missiological reflection, I described theological reflection as the beginning point of ministry. Missionaries (that is, all Christian leaders) must yearn to know the heart and motivation of God— what God is about in his world and why he is doing what he is doing—so that their ministry aligns with the purposes of God.

Theology is always contextual—always done within the contexts of living cultures. Thus this reflection describes the second arena of ministry formation—“cultural analysis.”

The question might be asked: “Why segment theological reflection and cultural analysis? Should theological reflection assume cultural analysis since theology must be done within living cultures?” The answer, of course, is “Yes!” In reality, however, it is easy for us to operate out of our own cultural bias, that is, projecting upon Scripture our own cultural paradigms of understanding. Thus missiologolists like Hwa Yung (Mangoes and Bananas: The Quest for an Authentic Asian Theology,”[i]), Kwame Bediako (“Jesus in African Culture”[ii]), and Samuel Escabar (“The Identity of Protestantism in Latin America”[iii]) seek to articulate the Gospel in the metaphors and cultural categories of their particular cultural contexts.

In Communicating Christ in Animistic Cultures I describe the difficulty of Western missionaries to not only understand but also communicate the Gospel into the philosophical presuppositions of animistic culture—where people perceive "that personal spiritual beings and impersonal spiritual forces have power over human affairs and, consequently, that human beings must discover by divination what beings and forces are influencing them in order to determine future action and frequently, to manipulate their power.” [iv] In this book I attempt to guide people to read the Bible with eyes wide open to the all-sufficiency of God’s work through Christ to defeat the principalities and powers (both personal and impersonal), and to live holy, faithful lives under the sovereignty of God. One prevalent theme is that Westerners attempt to domesticate Scripture to reflect their own secular heritages.

The questions thus become “How do we read Scripture to reflect the fullness of the kingdom of God in our cultural context? How do we faithfully communicate the Gospel and minister to human sinfulness and brokenness?” The technical word for this is contextualization, a term most vividly illustrated by the incarnation of Christ, who became God’s Word in flesh dwelling in our neighborhood speaking so that we can see and hear God’s glory, “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

Thus Christian ministry does not occur in a cultural vacuum; it takes place in cultural contexts, where rival perspectives of reality vie for human allegiance. Missionaries must therefore become adept at differentiating worldview types and discern how these types influence the host culture. These understandings enable missionaries to communicate God’s message so that it interacts with the culture’s perspective of reality.

In the next missiological reflection I will describe four distinct worldview types that are present and often intertwined in world cultures.

Frequently, church planters analyze bits and pieces of a culture but are unable to make a systematic cultural analysis. Or they effectively analyze culture in broad, general terms, such as pre-modern, modern, and post-modern, but are not equipped to make localized cultural analysis.

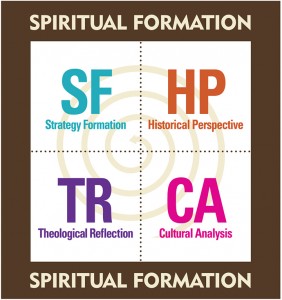

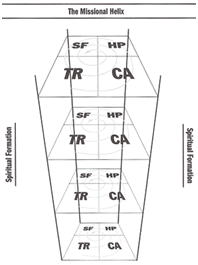

Overview of the Missional Helix

The Missional Helix visualizes ministry formation as a spiral. The coils turn round and round, passing the same landmarks, but always at a slightly higher level. This spiral, a helix, describes the process of effective ministry formation. The spiral begins with theological reflection – examining theologies which focus and form our perspectives of culture and the practice of ministry, such as the missio Dei, the kingdom of God, incarnation, and atonement. Cultural analysis, the second element of the Missional Helix, enables missionaries and ministers to define types of peoples within a cultural context, to understand the social construction of their reality, to perceive how they are socially related to one another, and to explain how the Christian message intersects with every aspect of culture (birth rites, coming-of-age rituals, weddings, funerals, and so on). The spiral then considers what has occurred historically in the missional context. Historical perspective narrates how things became what they are, based on the interrelated stories of the particular nation, tribe, lineage, the church, and God’s mission. Finally, strategy formation helps shape the practical methodology of ministry. The Missional Helix illustrates how contextual strategies draw deeply from cultural and historical understandings to theologically discern what God is saying about the practice of ministry and to then develop actual practices to implement the strategies. This shaping of ministry, however, takes place within the environment of spiritual formation as Christian servants humbly submit their lives to a covenant relationship with God as Father and enthrone Christ as their King.

The Missional Helix visualizes ministry formation as a spiral. The coils turn round and round, passing the same landmarks, but always at a slightly higher level. This spiral, a helix, describes the process of effective ministry formation. The spiral begins with theological reflection – examining theologies which focus and form our perspectives of culture and the practice of ministry, such as the missio Dei, the kingdom of God, incarnation, and atonement. Cultural analysis, the second element of the Missional Helix, enables missionaries and ministers to define types of peoples within a cultural context, to understand the social construction of their reality, to perceive how they are socially related to one another, and to explain how the Christian message intersects with every aspect of culture (birth rites, coming-of-age rituals, weddings, funerals, and so on). The spiral then considers what has occurred historically in the missional context. Historical perspective narrates how things became what they are, based on the interrelated stories of the particular nation, tribe, lineage, the church, and God’s mission. Finally, strategy formation helps shape the practical methodology of ministry. The Missional Helix illustrates how contextual strategies draw deeply from cultural and historical understandings to theologically discern what God is saying about the practice of ministry and to then develop actual practices to implement the strategies. This shaping of ministry, however, takes place within the environment of spiritual formation as Christian servants humbly submit their lives to a covenant relationship with God as Father and enthrone Christ as their King.

This missiological reflection thus encourages missionaries to perform an in-depth analysis of the local culture’s worldview. Much too often, this second element of the Missional Helix is excluded. Church planters naively project their worldview on other contexts and interpret reality in terms of their own heritage. This intellectual colonialism results in transplanted theologies, reflecting the missionaries’ heritage, rather than contextualized theologies, developed by reflecting on Scripture within the context of local languages, thought categories, and ritual patterns. Transplanted theologies are merely uprooted from one context and transferred to a new one, with the expectation that the meanings will be the same in both cultures. The beginning point of theologizing in a new culture is always a thorough analysis of the culture on a worldview level. With these cultural understandings, Christian ministers and missionaries are able to be theological brokers to people within the culture and minister alongside them in developing a local, contextualized theology.

In applying this missiological reflection, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the role of theological reflection in ministry formation?

- What is the role of cultural analysis?

- How are these two intertwined in ministry formation?

- What are the strengths and limitations of this missiological reflection?

You can read a full development of the Missional Helix in Chapter 13 of Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies (Zondervan/Harper Collins).

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen, Facilitator of Church Planting and Renewal

[i] Yung, Hwa. 1997. Mangoes or Bananas? The Quest for an Authentic Asian Christian Theology. Oxford, U.K.: Regnuun Books International.

[ii] Bediako, Kwame. 1994. “Jesus in African Culture: A Ghanaian Perspective” in Emerging Voices in Global Christian Theology, pp.93-126, edited by William A Dyrness. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan.

[iii] Escabar, Samuel. 1994. “The Identity of Protestantism in Latin America” in Emerging Voices in Global Christian Theology, pp.199-228, edited by William A Dyrness. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan.

[iv] Van Rheenen, Gailyn. 1991. Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts. William Carey Library, p. 20.

Blog

Blog